Posted originally on Planet of the Blind on June 29, 2019

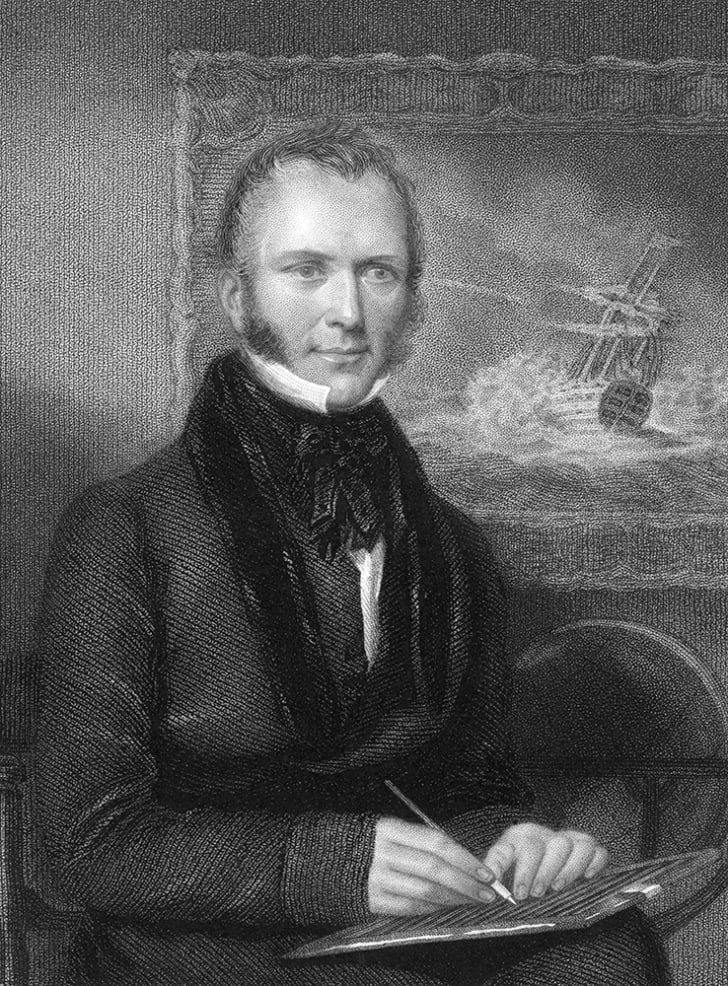

In his excellent biography of James Holman, “A Sense of the World: How a Blind Man Became History’s Greatest Traveler” Jason Roberts writes: “Until the invention of the internal combustion engine, the most prolific traveler in history was also the most unlikely. Born in 1786, James Holman was in many ways the quintessential world explorer: a dashing mix of discipline, recklessness, and accomplishment, a Knight of Windsor, Fellow of the Royal Society, and bestselling author. It was easy to forget that he was intermittently crippled, and permanently blind.”

I’m not sure about the forgetting. Though Holman’s celebrity dimmed over time, his blindness was always the point, and this is in part why we remember him now. I’ll venture to say he was the first disabled cultural diplomat, someone who implicitly recognized disability as a way of knowing, disability as epistemology. As a legally blind poet I believe getting lost is an art form. Holman is my great, foundational ancestor. Let’s put him on the blind Mt. Rushmore with Homer, Milton, Annie Sullivan, Helen Keller and Ray Charles. BTW: I think Homer was several people, all of them women.

All disabled life is performance. When a person is consigned to stasis through warehousing, lack of accommodations, insufficient health care, lack of education, steepened cultural dynamics (a disabled child is hidden so as not to affect the prospects of a sibling’s arranged marriage) the disabled performance signifies uselessness. As the American novelist William Gass once wrote: “culture has completed its work when everything is a sign.” I imagine Gass was being ironic since culture is a river as Heraclitus tells us. We enter it but never at the same point. Even Keats whose name is written on water can’t signify the entire river. The point of course is to enter it.

There’s no reason why the experiences of travelers with disabilities should differ markedly from those without. The imaginative and/or experiential discoveries of the disabled are lyric ones–unforeseeable and unique. Holman observed most sighted travelers didn’t see much. Attention isn’t the sole province of the sighted. This is obvious to those who teach disability studies, performance studies, or any form of cultural studies. The individual–whoever she is–brings attention, empathy, analysis, surprise, wonder, sorrow, and a myriad of archetypes to every encounter and so it must be also with those of us who are cripples. Disability scholar and performance artist Petra Kuppers, referring to disability dance workshops puts it this way:

“…’subjective’ bodily engagement is tacit in the process of trying to make sense of another’s somatic knowledge. There is no other way to approach the felt dimensions of movement experience than through the researcher’s own body.”

(See Petra’s wonderful book: “Disability Culture and Community Performance.”

Disability is somatic knowledge and disability travel is always a cultural enterprise–not as William Gass would have it, a matter of static signs–disabled movers are the purveyors of somatic knowing which is in turn the moving imagination.

**

Disability as cultural diplomacy is a grassroots enterprise. One shouldn’t confuse it with say, Van Cliburn. Remember? He was a gangly twenty three year old music prodigy from Texas who in 1958 improbably won the first international Tchaikovsky piano competition in Moscow.

Because the Cold War was in full swing Van Cliburn became a global celebrity and to this day he’s the only classical musician in American history to receive a ticker tape parade in New York. I should point out that Luciano Pavarotti once served as the grand martial for Manhattan’s Columbus Day Parade. He rode a herniated horse up Fifth Avenue. But that’s not quite the same thing.

Cultural diplomacy is many things of course. It’s been a determined product of states or state influence throughout history–artists and intellectuals, inventors have traveled at the behest of governments as de facto advertisements for the advantages of French language, Abstract Expressionism, jazz, Italian opera, Malaysian ballet, Russian poetry, you name it. One may say that all of Pablo Neruda’s career was a matter of cultural diplomacy. Refugees are also cultural diplomats.

What is the disability dynamic of cultural diplomacy? In her book “The Diplomacy of Culture” Irena Kozmyka writes:

“Since the end of the Cold War, culture and identity rather than ideology have been increasingly recognized as key forces shaping global order. The rise of identity politics and religious revivalism have been feeding debates on the “clash of civilizations” and Islam’s challenges to the West. In parallel, debates have been focusing on globalization, broadly defined as an empirical process of increasing worldwide economic, political, technological, and cultural interconnectedness. Globalization’s impact on culture has been viewed as both a blessing and a curse: on the one hand offering unprecedented opportunities for interactive and enriching cultural exchanges and therefore increasing cultural diversity, and on the other leading to uniformity or tensions between cultures.1 In many parts of the world, globalization is perceived as a threat to national cultures and traditional forms of identity.2 As a result and contrary to earlier predictions of “the end of history,” the forces of globalization appear to be more nurturing than destructive of the reaffirmation of sovereignties and, in reaction, of the demands for recognition of regional and local differences.

In these conditions, managing cultural diversity is increasingly becoming one of the major issues and concerns of the day, intrinsically linked with international security, social cohesion, and development. Indeed, cultural diversity at the international level overlaps with the now extensive debates on multiculturalism within states.”

Nation states are increasingly focused on historically marginalized people, and though this isn’t universal, as state oppression proves, disability is increasingly viewed as an important factor in interconnectedness. Milton C. Cummings describes ‘cultural diplomacy’ as: “the exchange of ideas, information, values, systems, traditions, beliefs, and other aspects of culture, with the intention of fostering mutual understanding”.

**

Quoting the philosopher Jean Luc Nancy, Petra Kuppers writes:

“Community is what takes place always through others and for others. It is not the space for the egos ‘subjects and substances that are at bottom immortal’ but of the I’s who are always others (or else are nothing).”

A crip community therefore is not the autonomous push and pull of national relations but a field, much as poetry is a field. One is reminded of the American poet Robert Duncan’s “Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow”:

Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow

as if it were a scene made-up by the mind,

that is not mine, but is a made place,

that is mine, it is so near to the heart,

an eternal pasture folded in all thought

so that there is a hall therein

that is a made place, created by light

wherefrom the shadows that are forms fall.

Wherefrom fall all architectures I am

I say are likenesses of the First Beloved

whose flowers are flames lit to the Lady.

She it is Queen Under The Hill

whose hosts are a disturbance of words within words

that is a field folded.

It is only a dream of the grass blowing

east against the source of the sun

in an hour before the sun’s going down

whose secret we see in a children’s game

of ring a round of roses told.

Often I am permitted to return to a meadow

as if it were a given property of the mind

that certain bounds hold against chaos,

that is a place of first permission,

everlasting omen of what is.

Disability is itself a disturbance of words within words; it’s filled with evanescence, indeterminacies, longings, strange permissions, properties of the mind that are both chaos and bounds against it.

When I wrote my collection of poems “Letters to Borges” I was conscious of this cripple’s principle–an ars poetica–that getting lost is a strange permission, and for me as a man who’s struggled to become an independent traveler an everlasting delight. I knew that Jorge Luis Borges never learned to travel by himself and wished to convey to his spirit something of the intellectual joy of wandering blind. Here’s a poem called “Letter to Borges from Estonia:

“Where I go is of considerable doubt.

Winter, Tallinn, I climb aboard the wrong trolley.

Always a singular beam of light leads me astray.

After thousands of cities I am safe when I say, “It is always the wrong trolley”—

Didn’t I love you with my whole heart? Athens? Dublin?

Solo gravitational effects: my body is light as a child’s beside the botanical garden’s iron fence—

But turning a corner one feels very old in the shadow of the mariners’ church.

I ask strangers to tell me where I am.

Their voices are lovely, young and old.

Yes, I loved you with my whole heart.

I never had a map.

Coordinated, Platonic movement in deep snow.

Crooked doors and radios in the bread shops.”

Back to Jean Luc Nancy: “Community is what takes place always through others and for others. It is not the space for the egos ‘subjects and substances that are at bottom immortal’ but of the I’s who are always others (or else are nothing).”

When I ask strangers where I am, I’m engaged in discovery not need, beauty not loss. This is the James Holman effect. One mode of somatic knowledge is thriving in the unknown. My wanderings Un-sign the signs. The antithesis of William Gass.

Cultural diplomacy is many things. But let’s suppose for the sake of argument that the U.S. State Department has it right. In a 2005 white paper they wrote:

“Cultural diplomacy is a two-way street: for every foreign artist inspired by an American work of art, there is an American waiting to be touched by the creative wonders of other traditions. Culture spreads from individual to individual, often by subterranean means; in exchange programs like Fulbright, Humphrey, and Muskie, in person-to-person contacts made possible by international visitor and student exchange programs, ideas that we hold dear—of family, education, and faith—-cross borders, creating new ways of thinking.”

As a blind writer who’s written about traveling the world by ear I’m attracted also to this from the State Department:

“To practice effective cultural diplomacy, we must first listen to our counterparts in other lands, seeking common ground with curators and writers, filmmakers and theater directors, choreographers and educators—that is, with those who are engaged in exploring the universal values of truth and freedom. The quest for meaning is shared by everyone, and every culture has its own way of seeking to understand our walk in the sun. We must not imagine that our attempts to describe reality hold for everyone. Indeed the history of art and literature is an essay in cross-fertilization. And American culture gains from its dialogue with the artistic and intellectual riches of other cultures. American artists who travel abroad, in official and unofficial capacities, are cultural diplomats who make incalculable contributions to the body politic. As Joan Channick notes: “Artists engage in cross-cultural exchange not to proselytize about their own values but rather to understand different cultural traditions, to find new sources of imaginative inspiration, to discover new methods and ways of working and to exchange ideas with people whose worldviews differ from their own.”

From a disability perspective one finds through travel that poverty, lack of educational opportunities, inaccessible architectures and social policies are obstacles to inclusion across the globe. One also finds that disability art, when taught from a place of empowerment, taught for and with disabled students creates crip space: a language, a field of somatic knowing.

Not long ago I spoke with blind children in Nur Sultan. Will I be called an inspiration pornographer when I say they were beautiful? The small girl in a white dress with angel wings sang a song. An equally tiny boy who was dressed like latter day Elvis also sang his heart out. Teachers brought forward a blind autistic boy who spontaneously added large sums. None of them had much in the way of orientation and mobility skills. They were talented and were led about. I was a foreign blind poet who felt himself shivering apart like a packet ship. I was aground on a reef of hardship. Parents wanted to know how I made it as a blind student and I had to tell them the way is hard—had to say the blind must work steadfastly and without pause; that in many instances we must work harder than sighted people. Even then we need luck and love. In Kazakhstan disabled children are largely segregated and though the Kazakhs have signed the UN Charter on disability rights—in effect committing their nation to disability justice—the way forward for the disabled is still steep and this is true in my own country god knows. One thinks of all the universities in the US that still adopt inaccessible software and course materials; colleges that imagine the disabled are structurally “apart” from student life. “Isn’t there a special office for them?” One shouldn’t imagine that with our mighty ADA and the UN Charter on disability rights we’re now living in a shining city on a hill. But I heard small children singing and I thought of Emily Dickinson’s remark about the writing of poetry, that the imagination is akin to whistling as we walk past a graveyard. It’s best to sing. Silence is privilege.

The imagination does not transcend disablement or color or ethnicity or gender. But as the American poet W.S. Merwin once pointed out—“it”—imagination—“lives up here and a little to the left.” Poetry is clear like the clouds in a Tintoretto painting and each of us has access to this. When we come down from this space we’re refreshed. Intellectual refreshment is a human right.

The disabled imagination is a human right.

Here’s a poem by the American poet Jillian Weise author of “The Amputee’s Guide to Sex”:

Some Rights

Right to property

Right to protect property

Encrypt everything

Make private

I am so right and if I’m not

I’m gonna burn yr FB wall down

Be something for sale

Be a strategy

Last fall was tough on us

Ask after me

Ask after me again

Small business owners

Big pharma

There are said to be 7000

bodies buried under

that university

If we write, it’s identity

If they write, it’s Reflections

on American Legacy

The ADA

Those aren’t just letters

Punk a bunch of coffins

Of this poem she wrote:

“The State is slowly and deliberately trying to extinguish disabled people through any means possible: erosion of our human rights, suspect ‘right to die’ legislature, denial of access to health care, etc. I’m alarmed when writers collude with the State. I wrote this poem as an objection to both the State and the ableism in poetry.”

**

In Almaty, Kazakhstan student poets, dancers, and musicians come together and perform their work as part of the disability and cultural diplomacy workshop my friends and I have been teaching. As a teaching poet I’m after art not the reductiveness of identity. Our students both have and do not have disabilities and to the best of my knowledge, have had no inclusive engagement. So we started out by dancing in a large public space; circling; bending; reaching; dipping; swaying; going low; wide; small; and very large.

As the American poet Elizabeth Bishop knew, the imagination has cardinal points but far more than the average map indicates. We’re making new maps for our insides.

My teaching colleagues include the superb choreographer and dancer Michelle Pearson, poet and nonfiction writer Christopher Merrill, novelist Cathleen Dicharry, and the world class jazz composer and musician Damani Phillips. Our trip has been sponsored by the U.S. Department of State and the International Writing Program of the University of Iowa. Cultural diplomacy in this case means inclusive arts education. But that phrase can’t capture what happens. In my class yesterday a woman wrote a poem about living in a sustaining star. We’d been talking about how poetry lets us imagine places that can’t be seen or drawn with a pencil. We’d been talking about inner freedom. We talked about many things: W.H. Auden, Andrei Voznesenskii, Emily Dickinson, Whitman. We wrote together. And then an neurodiverse woman took us inside the sun.

When, during a trip to China I find myself talking about poetry and dragons with blind teenagers suddenly everyone is flying across the sky and sewing poems in the clouds. This is cultural diplomacy and crip consciousness. I tell them as a blind poet I spend my time putting words in clouds. They get it.

It ain’t easy street because normalizing practices in speech tend toward the elimination of complexity and what is disability after all but convolution? Disablement is the ear inside the ear, folded, curly, wildly perceptive, and inapparent on the common street. That is how it is. That deaf woman, that wheelchair man, the blind walker—all are more cunning and imaginative than we may know, or better than normality will admit. Those of us in the disability studies arena talk about disabilities as ways of knowing precisely because as rhetorician Jay Dolmage notes, we understand “imperfect, extraordinary, non-normative bodies as the origin and epistemological homes of all meaning-making.” Imperfect and extraordinary are not “of” or “pertaining” to custom in Western thought, though as Dolmage demonstrates in his wonderful book Disability Rhetoric one may peel back the layers of storying and find examples of disability as a generative principle. Or, as Kurt Vonnegut once said, (and here I’m paraphrasing) “a story is interesting if a nun has broken dental floss trapped between her teeth…) Vague or overt discomfort generates all stories. But disability is less of plot and more of mentation. Disablement is metaphorically evocative. Precisely because it isn’t easy, disability is contentious to the body politic which always hopes to ignore disability perspectives in favor of delimiting narratives—whether we’re talking about a bad novel with a forlorn disabled character or an IEP for a student. Making disability “easy” is to not admit it into either a complex theoretical, imaginative or practical arena. Who among us disabled hasn’t been pressured in many a circumstance to say disability is easy? “Oh, it’s nothing,” we say, because the literal, daily experience of disability both inconveniences normal thinking, and because we feel always the implicit demand to project overcoming, which in terms of narrative, is always easy—you kiss the prince, pull the brass ring, you go home richer.

The lead casket in The Merchant of Venice bears an inscription on its lid: “Who chooseth me must give and hazard all he hath.” By Shakespeare’s time hazard was understood to mean chance of loss and as a noun it meant an unfortunate card. Such is the dominant appreciation of disability—a bad draw—but to hazard at lead is illustrative of doubling misfortune, to play a steeper gamble, to bet everything on a third class chance or ticket.

Hope is a hardened choice.

Let us assume blindness is never static and always takes its meaning in phenomenological terms from movement. Let us describe blindness as “Proleptic Imagination. ”

Proleptic: In rhetoric the anticipation of possible objections in order to answer them in advance.

Traveling blind is a performance both within normative subventions of assistance and outside cultural denotations of helplessness. Blind travel, taken as performance, is proleptic, both anticipating and answering implicit objections to the concept of blind independence in the very process of navigation.

In the restaurant that doesn’t want me I’m an inscription. It says on the lid of my casket: I doubled misfortune by moving. I transformed you who saw me by my very presence. Hazard is hope. Hope is hazard.

Motion is script. Moreover it’s lyric writing—by writing we discover our subject. Lyric discovery means disability was never what was thought, was never static, was always moving both physically and in the mind.

Let’s be clear: lyric imagination is never helpless. It’s incapable of dishonesty. It’s every discovery is just that: a pure finding.

In the city of Almaty I watch as my colleague Damani Philips leads an inclusive workshop on jazz. Every student plays his or her favored instrument. There’s an electric piano, a bass guitar, a violin, but what’s best is that everyone sings. They sing a song that just hours before did not exist.